Are there significant differences between the turnover or burnout of black female principals at K-12 schools labeled as having lower socioeconomic status and academic performance versus their counterparts at non-Title One or lower academic performing schools? How does this impact student achievement?

Research Questions

- What practical techniques can school districts use to prevent principal burnout in Title One schools and turnover for minority women?

- What are the main factors that influence principals’ decisions to leave the principalship before their scheduled retirement?

- How can school districts support Title One women principals after a significant crisis or interruption in learning?

- What currently exists for minority women to prevent burnout? What programs are already out there?

- How important is it to retain highly influential women in Title One Principalships?

- What impact does minority women leadership have on student achievement and school culture when you lose this specific demographic of leaders?

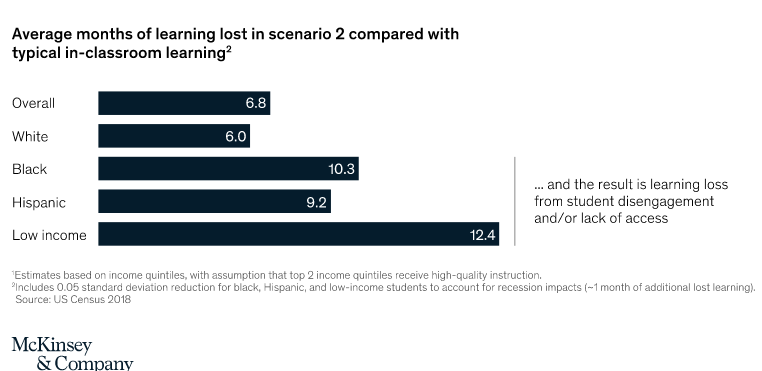

The onset of the Covid 19 pandemic, the political climate, and the constant attack on public educators has led many educators to leave the field and pursue other careers or retire early. Nittle (2022) said that the continuous changes in instructional models, distance learning, work-related stress, and the focus on SEL and mental health issues have made for a very challenging environment. Minority leaders feel judged based on everything, from how they dress and speak to how effectively they lead their schools. The constant stress has led many minority women to leave the field. The continuous shifts in job placements and assignments based on the needs of larger school districts may cause those in the principalship to question whether they want to continue daily. Developing a “Why” confronting your concerns head-on and taking time to reflect while relying on your support system is critical.

Burnout is inevitable when a leader is overwhelmed with work that does not contribute to their inner purpose. If you find this becoming your reality, reexamine your “why.” Determine if a career as a leader corresponds with that purpose. If not, it becomes incumbent on you to determine why not- and make whatever adjustments you need to move forward once again and walk in your purpose (Kafele, 2018).

Building Relationships and principal turnover

Principal turnover is defined as one principal exiting a school and being replaced by another. (Boyce & Bowers, 2016). Principal turnover can impact teacher turnover at the school and create a never-ending situation that does not benefit the students. When other positions at the school center are assigned to other people, the principal is more focused on student learning. In addition, building relationships and managing district and state policies can lead to frustration and a lack of continuity with the work. The research suggests that many factors contribute to turnover, including public vs. non-public schools, age, race/ethnicity, school, grade level, school size, student achievement, and the number of highly qualified teachers .(Boyce & Bowers, 2016).

Principal Preparation Programs, Retention, and support

Level II certification for the principalship with the state is required for those who wish to hold a principal certificate within the state and work at a public school in the role of principalship. Each district follows the state plan and provides critical tasks, assignments, and assessments during a one or two-year period with a required internship in alignment with the Florida Principal Leadership standards. Once principals complete the required program in their given district, they can apply for their principal certification and begin applying for jobs, but what happens next? What other support do we offer principals once in the role? How can we ensure they are successful, especially those who work in most high-needs schools?

Sustaining and supporting a strong administrator is key to the success of a school. The administrator role is constantly shifting, and several factors determine whether the staff feels supported; staff buy-in, professional development, technical support, shared vision and expectations and reaching of desired outcomes (Strickland-Cohen et al., 2014). One of the major barriers to administrator sustainability is the constant turnover in the role of principalship. When a school has a committed administrator, the staff will hold strong to the goals and vision, but when that person leaves, particularly in the early stages, the staff loses momentum (Strickland-Cohen et al., 2014). The constant mandates, district meetings, new trends, and policies make matters even more difficult for principals. The heavy load on principals is forcing many to walk away. The long-term recruitment and retention of highly effective principals that support student achievement rest on the shoulders of the district and how they best support their new principals.

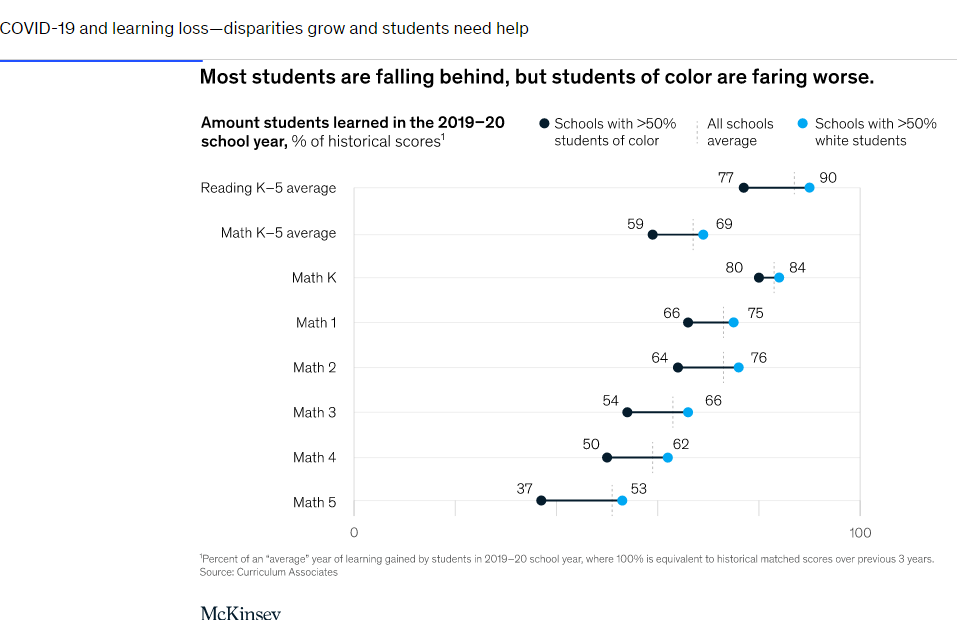

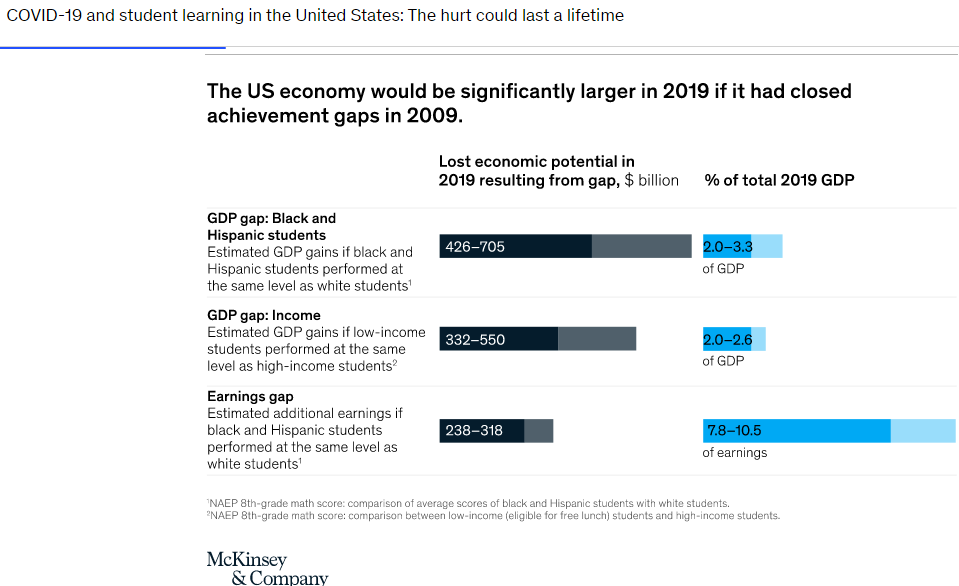

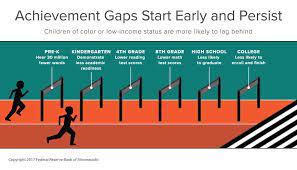

Academic Achievement and the principalship at higher needs schools

How are districts supporting students in higher-needs schools? Principals in high-needs schools face constant turnover as they work to improve teacher capacity and student achievement while also establishing positive working relationships with students and staff alike (Grissom & Dematthews, 2020). High rates of turnover consistently hurt schools as principals are constantly changing. Comparably schools with smaller lower income populations experienced less turnover and had more experienced principals within their buildings. The high turnover at high-poverty schools with lower student achievement was more likely to have more inexperienced principals with lower academic achievement. Still, as time went on, those principals stuck around versus being promoted or going into a central -office role.

Summary

Black principals serve schools with high percentages of students eligible for free and reduced lunch and with higher minority or student of color populations leading to perceived academic achievement or lack thereof (Sung Jang & Alexander Nicola, 2022). The researchers examined the demographics of several secondary schools, principal instructional behaviors, collective responsibility among the teachers, and their association between the interacting identities and the math achievement of the 9th-grade students (Sung Jang & Alexander Nicola, 2022). The research found that black women principals were associated with higher levels of teacher collective responsibility as perceived by teachers and higher math scores amongst students (Sung Jang & Alexander Nicola, 2022). The researcher found that quantitative research on black women principals was lacking, and their perspectives are often ignored or dismissed, seldom becoming part of administrative leadership theory. The writers determined that “institutional silencing” caused many black principals to feel unappreciated and out of place and led to severe misunderstandings, misconceptions, and stereotypes regarding school leadership and schools as a whole (Sung Jang & Alexander Nicola, 2022).