“Fortune favors the prepared mind.” – Louis Pasteur

Education has long been considered an essential tool for improving the plight not only of the individual, but of society as a whole. Educators and reformers from Socrates to Horace Mann to John Dewey have emphasized the importance of an educated populace as a means of perpetuating and improving a democratic society. Yet, how many times has an educator been heard to say, “This student just isn’t college material”? It may be true that during the Industrial Era schools were used to ‘sort and select’ leaders from workers, but we must ask ourselves whether this should be a function of our educational system nearly two centuries later. The world has changed substantially – but have we?

Regardless of whether a student has decided on a clear path to an occupational license of some sort, or whether they are positive they will be attending a specific college, or especially if a student is unsure of their future – the question remains: whose place is it to determine the trajectory of a student’s college or career path? I would argue that the skills needed for college and career are not substantially different and that it is our job as educators to adequately prepare all students so that they have access to options and are empowered to make their own choices about post-secondary opportunities.

In today’s economy, a post-secondary credential is in greater demand than ever before. In remarks made by President Barack Obama at Pellissippi State Community College in 2015, he indicated that now more than ever, a college degree is the key to getting a good job that pays a good income, and provides long term job security (The White House, 2015). His claim echoes predictions by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, indicating that, by 2018, nearly two-thirds of jobs in America – approximately 63 percent – will require workers with at least some college education. About 33 percent will require a Bachelor’s degree or better, while 30 percent will require some college or a two-year Associate’s degree. Only 36 percent will require workers with just a high school diploma or less (Carnavale & Smith, 2010). Whether students choose to further their education through college, apprenticeships or other kinds of on-the-job training, “all high school graduates will definitely be held to a higher intellectual standard than ever before” (Achieve, Inc., 2004, p. 107).

This growth in the demand for post-secondary education stems in part from the fact that the fastest-growing industries are technology related, requiring workers with disproportionately higher education levels. However, even among jobs that are not technology related, occupations as a whole are steadily requiring more education. Some form of postsecondary education or training has essentially become the “threshold requirement” for access to middle-class status and earnings (Carnavale & Smith, 2010). Postsecondary attainment is even more significant for the lowest income Americans who are five times more likely than their peers to escape poverty if they complete a college degree (National College Access Network, 2015).

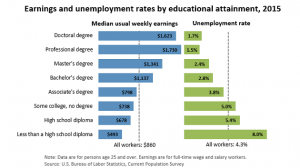

Source: (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016)

Source: (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016)

There is a persistent notion that students going into the workplace need a completely different curriculum than students on a college preparatory track, yet the types of skills and knowledge needed to be successful in either college or career are actually quite similar. While the specific academic content may differ, critical thinking and problem solving skills, as well as the ability to work with others are common necessities for all students whether they are seeking to enter college or the labor force.

A report by the American Diploma Project (ADP) indicates that college readiness and career readiness skills are more convergent than divergent. In 2004, the American Diploma Project established a series of standards and benchmarks that defined the necessary knowledge and skills for both college and workplace success through partnerships with both employers and faculty at two- and four-year colleges (Achieve Inc., 2004). First, ‘good’ jobs were defined as those that paid well enough to support a family and that had the potential for career advancement. Using these jobs as a baseline, the required competencies needed in both high school and college courses appropriate to these jobs were used to back-map and create a series of aligned standards for grades 4 to 12 to indicate the academic skills needed to be on track to both college and career readiness (Achieve, Inc., 2004).

Unfortunately, it appears that we are not preparing all of our students for post-secondary success. Many enter college unprepared for the demands of postsecondary education and, as a result, encounter discouragement and never complete their degree. Almost half of all U.S. college students fail to graduate, even though they satisfy their colleges’ admission criteria (ACT, 2015). Students who require remediation are at greater risk for dropping out of college. Those who require a remedial class graduate at a rate between 30 and 57 percent, depending on the type and number of remedial classes they take, as compared to students who do not require remediation and graduate at a rate of approximately 69 percent (NCES, 2004). Worse, Avery and Daly noted that for Hispanic and African American students, “the journey through college toward a degree, successful career, and promising future, is more likely to resemble travel through a sieve than an educational pipeline” (Avery, 2010, p. 46). Independent of the type of institution, educational equity with regard to outcomes is absent: White and Asian students tend to graduate at higher rates than Hispanic and African American students with the largest gaps between Whites and African Americans (20.8%) and Whites and Hispanics (16.5%) (Avery, 2010, p. 49).

It is clear that a lack of college readiness costs students immensely – not just in terms of time and tuition but in terms of future job potential and lifetime earnings. Students headed for careers directly from high school don’t fare much better. According to the American Diploma Project, 60 percent of employers are of the opinion that students coming from high school to the workplace have poor essential skills, requiring additional training and remediation in the workplace which costs employers nearly $40 million per year (Achieve, Inc., 2004, p. 107).

Thus not only does a lack of college and career readiness cost students and employers, but it represents a cost to society as a whole. At the third annual Brown Lecture in Education Research, Linda Darling Hammond emphasized that students “who are undereducated, [particularly low-income students of color], can no longer access the labor market. While the United States must fill many of its high-tech jobs with individuals educated overseas, a growing share of its own citizens are unemployable and relegated to the welfare or prison systems, representing a drain on the nation’s economy and social well-being, rather than a contribution to our national welfare” (Darling Hammond, 2007).

With postsecondary success so closely tied to future income and employability, and remediation so closely tied to college completion, it is critical that students enter postsecondary life – whether at a university, a state college, an occupational license program, or the world of work – prepared with the skills necessary for success and without the need for remediation. It seems then, that as educators we should focus on educating all of our students to an equally high standard, providing equitable access to the curricula and academic opportunities that will allow them to be adequately prepared for whichever choice they decide to make.

Works Cited

Achieve, Inc. (2004). Ready or Not: Creating a High School Diploma that Counts. Achieve, Inc., The American Diploma Project, Washington D.C. doi:http://www.achieve.org/files/ReadyorNot.pdf

ACT. (2015). National Collegiate Retention and Persistence to Degree Rates. American College Testing Program. ACT, Inc. doi:http://www.act.org/research/policymakers/pdf/retain_2015.pdf

Avery, C. M. (2010, Winter). Promoting Equitable Educational Outcomes for High-Risk College Students: The roles of social capital and resilience. Journal of Equity in Education, 1(1), 46-70.

doi:http://digitalpubs.nyu.edu/jee/article/view/14

Carnavale, A., & Smith, N. a. (2010). Help Wanted: Projections of Jobs and Education Requirement through 2018. The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University. Retrieved July 29, 2015

Darling Hammond, L. (2007). The Flat Earth and Education: How America’s Commitment to Equity will Determine our Future. Educational Researcher, 36(6), 318-334. Retrieved October 10, 2015

National College Access Network. (2015). Retrieved July 29, 2015, from National College Access Network: http://www.collegeaccess.org

NCES. (2004). National Center for Education Statistics.

The White House. (2015, January 9). doi:https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/09/remarks-president-americas-college-promise

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016, March 15). United States Department of Labor Statistics. Retrieved March 26, 2016, from United States Department of Labor: http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm

I was extremely surprised by the data in the unemployment chart. I had no idea it was a direct correlation to level of schooling, wow!

I was talking about this with a colleague just today! He was saying just that, how not every student was meant to go to college and that we should have two trajectories in high school, one towards trade or occupation and that other towards university. We certainly do need more career academies, so that that students can leave high school trained in something like dry walling, electrical work, mechanical engineering, etc. However, you make a very important point, that in today’s economy even many of these blue collar jobs are requiring some level of education past high school. We should be focusing on making students college ready and not pigeon holding students to one path or another.